One pressing question that is at the forefront of my mind as I consider lesson planning, content delivery, and the alignment of my teaching with my philosophy as a progressivist educator is this: how can I maintain a balanced representation of perspective and experience when teaching the humanities? The incorporation of multiple, coexisting, and/or simultaneous realities when examining the past and present is what makes the humanities (and really anything, for that matter) worth studying. A large part of my senior thesis for my American Studies/History program last semester highlighted the importance of teaching World War I through the eyes of those who experienced it and its repercussions, not only from the trenches, but also on the homefront, during the interwar period, and beyond. The fact that experiencing history was and is not limited to white voices, white authored textbooks, and old white men who started wars is enough of a reason for students and teachers to demand a wide range of representation in their studies for the sake of learning whole truths with the added bonus of diverse mediums. Studying the soldiers of the Great War’s trenches is entirely beneficial to one’s world history education, but there is so much more to war than the literal fighting. Celebrating MLK, Jr. (as my class did last week) is great for diversity awareness and inclusion, but taking one day out of 180 to look at diversity is not equivalent to championing an equitable and socially just curriculum. This week, my students continue their studies of westward expansion in the United States; however, I created a multi-day lesson that my cooperating teacher and I will layer into his own lesson plans, filling in some diversity gaps that our original plans would have left wide open. This week, we are talking about the forced removal of Native Americans, and all of the harsh realities that came with it.

As a future educator, I know that the amount of time I will be able to spend on any given social studies/ humanities topic will depend on deadlines and standards. As a passionate historian and progressivist teacher, I aim to plan and implement lessons that fairly represent all perspectives and experiences of history, no matter how whitewashed popular sources may be. While there will never be enough time to adequately teach every possible angle of a historical event or literary text, I am committed to balancing as many realities and truths of historical study as I can in the classroom. My students deserve a diverse and inclusive take on education. History and soon to be history depend on it.

|

| Source: https://cdn.history.com/sites/2/2018/03/GettyImages-517330290.jpg |

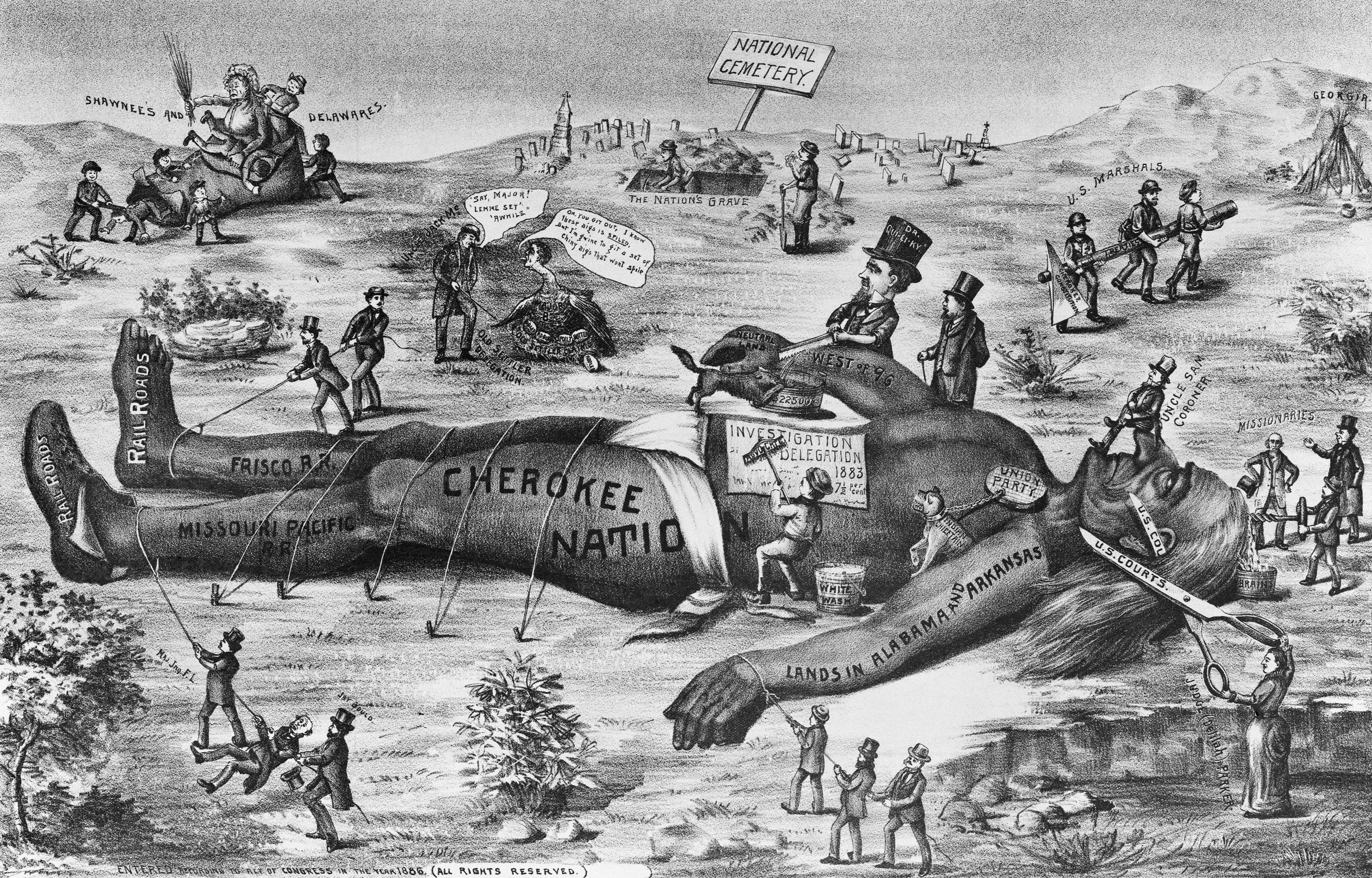

Our Native American perspective of Westward Expansion started today with the image above. Students were asked to write down what they noticed about the image in a few sentences, from the people in the picture to the words written all around. After a few minutes of private reasoning time, we discussed the image as a whole class, underscoring the portrayal of Native Americans in the image and the critical depiction of white settlers moving west. Of course, this image paints an entirely different picture than the “American Progress” painting I introduced students to at the start of our unit.

Students then worked on a mapping activity for the remainder of class, charting out the Trail of Tears and drawing in Native American tribal land borders within U.S. lines before expansion began. Tomorrow, students will complete another mapping activity, drawing in current Native American reservation lands in the United States. Hopefully, students will see just how significant the losses for Natives were post-expansion, and I look forward to discussing how much the Native population is still impacted by the white man’s dream of “Manifest Destiny” today. Following the mapping activities, students will read excerpts from writings that detail the Trail of Tears and white missionary work with the Native American population (particularly the Cherokee), as well as examine some before and after portraits of “Americanized” Native students attending white boarding schools between 1880 and 1900. Ultimately, my goal is to have students discuss the positive and negative impacts of fulfilling Manifest Destiny from all perspectives, and I believe this lesson will prepare students to argue both sides effectively and with fair representation.

As a future educator, I know that the amount of time I will be able to spend on any given social studies/ humanities topic will depend on deadlines and standards. As a passionate historian and progressivist teacher, I aim to plan and implement lessons that fairly represent all perspectives and experiences of history, no matter how whitewashed popular sources may be. While there will never be enough time to adequately teach every possible angle of a historical event or literary text, I am committed to balancing as many realities and truths of historical study as I can in the classroom. My students deserve a diverse and inclusive take on education. History and soon to be history depend on it.

Comments

Post a Comment