Happy New Year, Old Sport! That’s right, I am back in action with the start of 2020 (and hopefully, these ‘20s are even better than the Roarin’ ones!). The new decade also brings an early start to a new semester here at Saint Michael’s College for me and my fellow education majors. The beginning days of 2020 hold a lot of promise for me in particular, and I am hoping to keep up this initial momentum for an exciting year: I have started to pursue different publishing opportunities for a novel I have been working on since I was a senior in high school, I am eagerly waiting to hear back from the Fulbright Fellowship board about my pending application, and yesterday marked the first day of my last semester at St. Mike’s as an undergrad.

As a secondary education major, my final semester will be filled with the preparation, practice, and learning opportunities that naturally come with a hands-on student teaching internship. In order to better process and document my time as a student teacher, I plan to reflect on my experiences at EMS weekly through a series of student teaching (ST) blog posts. So, without further adieu, here is my wrap-up for week one (Of course, this week was shorter in observance of the New Year’s holiday. Most weeks will have more posts, as opposed to this week’s one.)

It’s the final two days of a unit centered around literary devices and how they are employed by poets in their written work. Students spent a few classes before their winter break writing multiple original examples of selected poetry genres, and many students finished editing their two favorite poems, decorating the poems on posters, and turning them in for assessment. Yesterday, Mr. J asked students to create a poster for a literary device they have reviewed in class. The posters will hang in our classroom and around the school hallways with student poetry as explanations for the students’ work. Each student blindly drew a literary device from an envelope to work on. When it came time for a student— let’s call her E— to pick her literary device, her exclamation made her discontent entirely clear: “How am I even supposed to do this? You can’t even draw a rhyme scheme!”

|

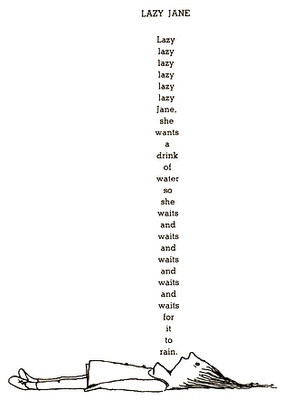

| From Shel Silverstein's Where the Sidewalk Ends. Silverstein is a master of drawing images that not only reflect his poems, but also the literary devices used within them. |

When I was in eighth grade, I probably would have struggled with the idea of drawing a representation of “rhyme scheme” too. For the literary device posters, students were asked to have a title (their literary device), an “easy to understand” definition of the literary device, and four written examples with pictures. Even as a college student, it took me a few minutes to think of a solid example that could be paired with a visual representation for rhyme schemes; however, I knew Mr. J gave examples of each literary device, and I was positive that E had access to the examples used in previous lessons. Did she not want to do the work? Did she lack an understanding of what rhyme scheme really was? Did winter break make the week-old poetry lessons seem far off in the distant past? When Mr. J asked E why she wanted to trade in her literary device, she explained that she thought drawing a rhyme scheme would be too hard. How do you draw a particular pattern of word placement? Well, eventually E switched her literary device to personification, but I did see several other students successfully complete a poster on rhyme scheme. Students were allowed to trade their literary devices with other students if both agreed on the exchange, but E seemed to base her preferences on how easy she felt it would be to draw an example of the literary device, not her understanding of the devices and their usage. Was this a matter of grit? Should students have been allowed to trade their literary devices in for another? If students were allowed to trade, why have them draw from the envelope at all?

While I think E’s decision to trade in rhyme scheme for personification was based mostly on her own beliefs in her ability as an artist, E’s explanation of rhyme scheme being too hard to draw seemed odd to me: in the two years that I have known her, she has never been one to shy away from a challenge. However, she also tends to react strongly when her confidence is shaken. Of course, completing the project with either literary device would bring her success in the classroom, but I wonder if E should have been encouraged to better research some examples of rhyme scheme before she chose to switch her poster topic. Mr. J always sets high expectations for his students, and E’s understanding of all literary devices studied in the unit had been demonstrated in the classes before winter break. Perhaps her mindset only seemed fixed in this moment, and her struggles with thinking of visual examples for rhyme scheme only demonstrate that E is not a visual learner— her intelligence lies elsewhere. For me, this moment brought up a single question: if students demonstrate an understanding of a topic, how much deeper should that understanding be pushed? In other words, should E have been pushed to draw examples of rhyme scheme, since Mr. J knew she had an understanding of the literary device, even when she said she felt drawing the examples would be too hard?

Initially, I was torn about whether or not E should have been encouraged to complete the poster project on rhyme scheme. She knew the literary device, its definition, and some written examples that did not necessarily lend themselves to easy visual representations. However, E clearly wanted to complete the project on a different literary device, and she was indifferent toward offered examples of visual aids for rhyme scheme. If she knew the information required for the poster, why push her to draw pictures she had no desire of drawing, especially when she was more willing to complete the project fully with another literary device in mind? As I considered E’s overall demonstration of her knowledge and understanding of the literary devices, the importance of her drawing out examples of rhyme scheme decreased. While in the moment I wanted to encourage E to work with the literary device she had originally chosen, I realize now that her completing the project to demonstrate an understanding of literary devices was not dependent on the device she chose. The unit’s summative assessment had already taken place, and E’s preference to perform within her own skill range using her new understandings of literary devices is arguably the best way to reinforce previous learning at an independent level. In the future, I hope to gain a better understanding of when students should be pushed outside of their comfort zones and/or supported during independent practice, particularly in relation to Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. For now, I am eager to continue my observations in Mr. J’s classroom and focus more on finding both the causes and effects of the key learning points throughout student teaching experience as a part of my professional development.

Comments

Post a Comment