Fall is again in the air here at Saint Michael's College, where flannels, a St. Mike's sweatshirt, and anything Patagonia or L.L. Bean tend to be the staples of low fifties to about seventy-degree weather. Yesterday morning, after I convinced myself that I would be more productive out of my bed than I would be under my warm blankets, I tugged on my own L.L. Bean jacket before heading to a short workshop run by a St. Mike's professor on teaching college students with disabilities. Showered by the falling of October's colorful leaves and enjoying the sun's warm light while I still can, my mind wandered to an incident from a few weeks ago that I have been thinking about ever since it happened, and as I arrived at the workshop, I was determined to learn as much as I could about adopting teaching practices that keep student disabilities in mind. After all, I would not want to put my own students into a situation similar to the one I recently encountered as a student in a classroom.

When I was six years old, my family and I discovered that I have a condition similar to cholesteatoma; an ear condition where dead skin cells grow over the eardrum for any number of possible reasons, often leading to hearing loss (the difference between cholesteatoma and my condition is that I do not have a cyst from which the skin cells grow). For me, chronic ear infections throughout my childhood along with the continual cell growth led to some permanent hearing loss in my right ear, as well as progressive hearing loss that can be reversed by removing the dead skin from around my eardrum every few months. If the procedure doesn't sound pleasant, it's probably not as bad as you're thinking. However, even with the skin removed and my hearing returned to its best possible range, I still struggle with identifying which direction sound is coming from, especially when the sound is created by a machine.

Now for the incident. For starters, I have never considered myself disabled. I don't wear hearing aids, and I have learned plenty of tricks for keeping up with a conversation when my hearing slips into its regular declines. However, watching movies in class has been an obstacle for me since first grade, particularly when the actors whisper or have heavy accents. Here is where the proactive teacher brain kicks in: this obstacle comes with the easy solution of turning on closed captioning. Well, there's another problem. Sometimes, I feel embarrassed when I have to ask for a teacher or professor to turn them on, especially when I know the captions can be a source of distraction for others.

About two weeks ago, I entered a class for the second day of watching a movie. I did not ask for the captions on the first day, hoping the volume and some desperate lip-reading would suffice for my understanding. There is another student who is hard of hearing in the class, and they seemed unbothered by the lack of captions. Was it appropriate for me to ask for the captions, even when a student with visible hearing aids didn't seem to need them? After I built up the courage to say something as the movie was placed on the computer's disk tray, I was somewhat shocked and caught off guard by the corrosive remark I received in response. I am not offended, and I felt in no way attacked, but I am disappointed by how my request was received. Long story short, closed captioning was turned on, but only after I was given the impression that it was humorous for me to ask outside of a foreign language classroom.

|

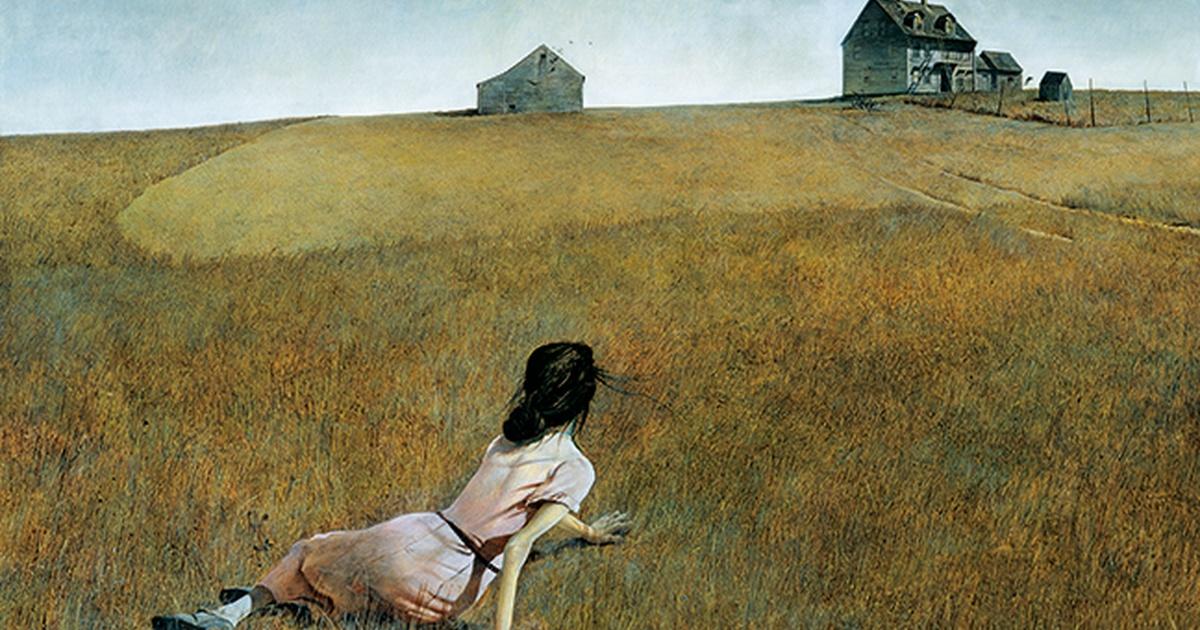

| Christina's World by Andrew Wyeth, 1948 |

Yesterday's workshop provided wonderful insight into the world of education as navigated by students and educators with disabilities. Presented by a professor of philosophy who uses a wheelchair, the workshop asked thought-provoking questions that urged participants to reevaluate their perceptions of identity and disability. As a group, attendees analyzed Christina's World by Andrew Wyeth, a beautiful painting that features a young woman and her daily challenges with mobility on her family's farm (pictured above). The young woman, Anna Christina Olson, was Wyeth's long-time, coastal Maine neighbor. Without knowing the painting's backstory, Christina's presence may look like any young woman's plight as the Great Depression weakened the nation back in the 1930s, but Wyeth's composition was completed in 1948. Suddenly, the details of Christina's feeble body are amplified as the painting starts to seem outdated (well, maybe not for 1940s northern New England, but you get the point). The truth behind Christina's World rests in her determination to move about independently after a childhood case of polio left her unable to walk. From the viewer's standpoint, that house seems a lot farther away now, doesn't it? Well, to Christina, crawling got her where she needed to be as freely as the vehicle that left the tire tracks in the background would have.

Several suggestions were made for improving teaching practices with disabilities in mind: purposeful classroom arrangements for easy mobility; person-first language and mirroring the language used by students with disabilities for describing their disability; mindfulness of lecture tools and habits that may be distracting or incomprehensible to students with ASD, hearing loss or deafness, blindness, and ADHD; the use of closed captions, visual/ audio supports, and body language to communicate a message or lesson; and so much more. Of course, practicing teaching strategies with student disabilities in mind is something I want to engrain in my work as an educator from the beginning of my career. However, I do know that teaching all students well will take time, dedication, and a lot of practice. The strategies and tips I learned from the workshop today are great stepping stones for developing my own adjustable teaching habits and growing as an educator who respects and considers all students' needs. I think Andrew Wyeth said it best when describing Christina's World: like Wyeth, I want to teach in a way that captures the extraordinary things my students do every day, just as he strove to "do justice to [Christina's] extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless."

You can read more about Christina's World here.

Curious about the workshop? Check out Professor Standen's presentation here.

Comments

Post a Comment